I can say that I have worked in different jobs throughout my life. I had different jobs, I did different things, I was the one in charge and I was also at the lowest rung of the work hierarchy, all jobs left me with something special and wrote an important chapter in the book of my life. My first job, although it did not help me much in improving my work experience, did leave me with unforgettable moments.

My first job was cleaning the windows of my dad's tailor shop.

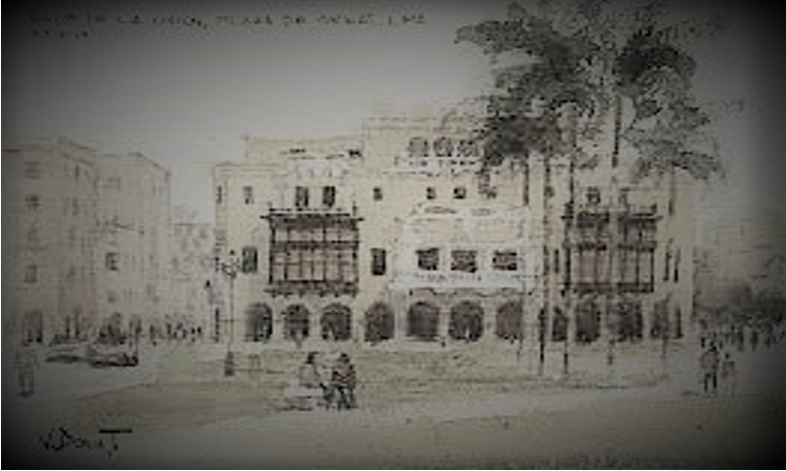

Sastrería Loli was the business that provided all the economic security that the family had. It was half a block from the Plaza Mayor of Lima, one block from the Government Palace and the Cathedral of Lima, and just a step away from the Lima City Hall. Because of its location, my father was able to serve presidents, politicians and "important" people on the local scene.

The business was very successful while the fashion of wearing suits on a daily basis lasted and especially when they were used for almost any occasion. Although my father did not participate directly in the making of the suits, he did other types of activities such as taking measurements, distributing the work, buying the cuts of fabric and other supplies that were needed for the making.

As for my job, after a quick training from my father, I started with the Saturday job which consisted of cleaning, one by one, the shop windows where combinations of shirts and ties, cufflinks for shirt sleeves, accessories and toiletries were displayed. In addition to the counters, the shop had two other large display cases where my brother showed us his good taste in decoration with his perfectly coordinated sets of sweaters, shirts and pants.

The windows I liked to clean the most were those of the large window that looked out onto the portals of the Plaza de Armas. I had to climb up there and clean them with the special liquid - I still remember its smell - and a beige cloth that, when I got to that point after almost finishing all my work, was usually completely wet. At the foot of that window was where, at the end of my day, I would take out of one of the pockets of my pants, two carts to begin my break playing solo.

A few meters from the window, there were almost always two or three street vendors selling alfajores, pencils, sixth-rate stamp paper for paperwork at the municipality, and sweets accompanied by the classic shoe-shine vendors.

During one of my games I noticed the insistent gaze of the lady selling alfajores, who smilingly watched me sitting on her little stool where she used to offer her sweets with a tray on her knees. I have a son about your age, she said. How old are you, boy? What is your name, son? she continued asking without stopping smiling. I'm going to bring him next Saturday so you can play.

Don't think that I forgot Carmen's promise - that's what I think her name was - and I waited for that Saturday with great anxiety. That day I cleaned the windows much faster than usual so that I could go out and clean the large window as soon as possible.

He greeted me politely, saying: My name is Victor, and you? He held out his hand to me. It was the first time someone had introduced themselves to me with such formality. My name is Pablo, I am six, I said, and he smiled.

Victor was a boy with a lively look, his gestures betrayed a propensity for intense activity, with straight black hair cut almost close to the scalp, with brownish skin ‒he once told me: we are almost the same color‒ he wore a plaid shirt and well-ironed jeans.

We played a lot with my cars. I remember that I had hidden six cars, and we played for a long time until I heard the sound of the metal curtains closing, announcing that it was time to go home for lunch. See you next Saturday, said Victor.

Many Saturdays passed like this, with Victor's presence becoming more and more familiar in my working world. We would go shopping together. Stay close to him, he's "more lively," my sister would whisper to me. We would wander around Jirón de la Unión, go up and down the escalators at Sears, which was one of the few department stores, and climb into the elevators at the Oechsle store, where the elevator operator always looked at us with distrust.

We would dip popsicle sticks in the pool in the square, we would drink sugar cane juice at his friend “the landlord Luis”’s place, and once he tried to treat me to a “cevichito” that he used to “mooch” from his mother’s street vendor friends. We would also play inside the tailor shop, we would go up and down from the attic to the basement, racing before the astonished gaze of my father’s employees who would murmur and question how the street vendor’s son could play with the owner’s son.

Victor was invited to my house for lunch and also to my seventh birthday party. I remember that he arrived well-groomed, dressed in new clothes that I had never seen on him before and with a gift in his hand that he gave me as soon as he walked in. I hope you like it, he said timidly.

After my birthday we saw each other again on a few more Saturdays and it was on one of them that Victor asked me if I wanted to go to a secret place that he was forbidden to go to, it's the pet market, but you have to cross Avenida Abancay, he told me; I've crossed it several times, but I don't know why my mom says it's dangerous. Let's go, I said. Let's go then, Victor replied happily.

Crossing Abancay Avenue was worse than I had imagined, but Victor skillfully positioned himself next to a couple who were crossing with their shopping bags, dodging all kinds of minibuses, cars, motorcycles and tricycles full of fruits and vegetables.

When we arrived at the famous pet market, a whole block full of exotic, wild and domestic animals awaited us in captivity in their cages. There was a bird section where the colorful macaws and albino cockatoos stood out. Within the exotic area there were monkeys the size of a hand, as well as a small feline - according to Victor it was a jaguar.

The domestic animals were predominantly small dogs whose ears had been glued down to make them look like German shepherds; they make good guard dogs, they announced.

We walked up and down the animal market several times and I remember feeling like I wish I had a big house and had all those animals to myself. Can you imagine if we let them all out? They look sad, I don't like injustice, he told me when we were already walking back.

The following Saturday I waited until the last minute to say goodbye. I was going with the whole family to spend the end of the school vacation season at my uncle Lucho’s ranch. I’m sure we’ll see each other again, he told me. Of course, I managed to say. I gave him, in a shoe box – hidden from my mother – three of the cars he liked to play with the most: the Batman one that shot plastic bullets, a grey James Bond one and the black Green Hornet car. Here, it’s for you, I said and gave him a hug.

I never saw Victor again, although sometimes he appears in my dreams, crossing Abancay Avenue with me and freeing, this time, all the animals from the pet market.

This story is dedicated to Victor Santisteban ‒55‒, cowardly murdered during one of the protest marches on Abancay Avenue against the government of Dina Boluarte. Victor was shot down by a tear gas bomb fired directly at him at very close range by a member of the Peruvian National Police.

You may be interested in: Hyperopia – or you barely discover your country when you are far away