By Eli Bartra and Liliana Elvira Moctezuma.

PRESENTATION

In these dismal times we are living in, people talk about THE pandemic all the time. But it is necessary to think that there is more than one: in Mexico the pandemic of feminicide is growing every day. Of course, calling it a pandemic is somewhat metaphorical because the concept itself means that it attacks all people, on a global level, and not, as in this case, that it only affects women.

A similar phenomenon happens when we talk about the Holocaust. There have been many genocides and holocausts, dozens of them throughout history and all over the world: there is not only that of the Jews by the Nazis. There were the Mongol invasions in the thirteenth century, which left some 11 million dead; the Muslim conquests in India in the fifteenth century produced 400 million dead and has been called the largest genocide in existence; that is, India suffered genocides, holocausts, by Arabs, Turks, Mongols, among others, for 800 years. At the end of the 19th century, in the Congo, Belgian colonialism exterminated 10 million people. At the beginning of the 20th century we have the holocaust of the Armenian people by Turkey in which some 2 million people died. And we must not forget the Stalinist Soviet holocaust (1924-1953) against the Ukrainian people, and other purges and atrocities, which claimed some 5 million lives.

Femicide is not a new phenomenon. What is relatively new is the concept and the proportions. Nor is that of raped women; perhaps they are as old as humanity itself.

Although violence against women has existed for a long time in Mexico, it has been practically invisible and even naturalized. In addition, women have had access to education and artistic creation for approximately 100 years, so it would be difficult for men to make it visible, unless it was to capture some specific facts, as José Guadalupe Posada did. It begins to express itself after the Mexican Revolution with a clear influence of the engraver, as in the cases of Isabel Villaseñor and Frida Kahlo.

As you can see in the examples we have selected of artistic practices from contemporary Mexico, the image of violence against women has been present since that time, in some expressions more and in others less.

Without any desire to compare, we will show works by both men and women, which we have considered significant for their aesthetic power, in order to shed light on their generic differences.

One of the main representations of violence against women in art is, without a doubt, feminicide. This is surely so because it is brutal, because it is extreme? beatings often have a solution, death does not, neither does feminicide. Art that depicts or denounces the problem of violence against women is intended to provoke discomfort and, sometimes, empathy. Discomfort when scenes of violence or elements that remind us of abused or even murdered women are explicitly shown. Empathy, when it reminds us of some who are no longer there due to situations of violence.

Since popular art tends to be made for a very particular market, if situations of violence were depicted, it might be more difficult to commercialize it. Often folk art tends to present repetitive themes in which such violent events and their denunciation have little place. However, it is likely that if popular artists had more creative freedom, it could then be a recurring theme given that, unfortunately, the fact of being a woman in Mexico almost necessarily implies having suffered some kind of violence: sexual, symbolic, labor and that derived from organized crime.

Artistic practices have a considerable influence on mentalities, on people's consciousness. The effects have been harmful, but they can also be very powerful and useful as a denunciation, as a challenge. That's why art has been used to communicate political ideas of all kinds. For example, the nude feminine contributes to the objectification of women, but it is also used to make a critique of its subjugating use. Feminism gives way to the appearance of works that denounce violence against women in all its forms. It has been absolutely crucial, that's why today there is a lot of feminist artivism, fundamentally political artistic practices of contestation.

PLASTIC ARTS

José Guadalupe Posada (1851-1913).

Francisco Guerrero, nicknamed El Chalequero, was a serial killer of at least 20 women during the Porfiriato. Posada made several engravings about his crimes, and it was one of the first representations that we find about the murder of women and that apparently served as inspiration for some later artists.

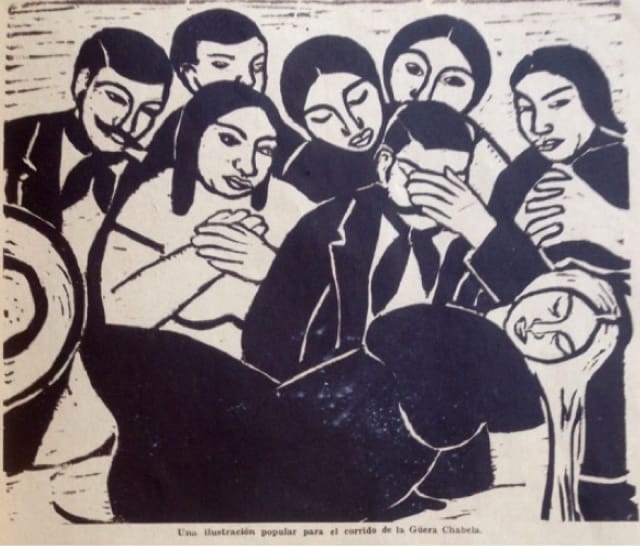

Isabel Villaseñor (1907-1954)

Jesus Cadenas told him:

I'm in charge of that blonde

I will give them satisfaction

Don't make any mistakes?

Fragment

She is one of the first representatives of feminicide in the art of Mexican artists. In her engravingo The Death of the Güera Chabela in 1929, Isabel Villaseñor illustrates a corrido written by Concha Michel. It recounts the murder of Güera Chabela at the hands of Jesús Cadenas, who finds her dancing at a fandango with other men and shoots her four times in the heart for being a ?mancornadora? Villaseñor portrays Güera Chabela's family as her father, mother and other partygoers mourn her.

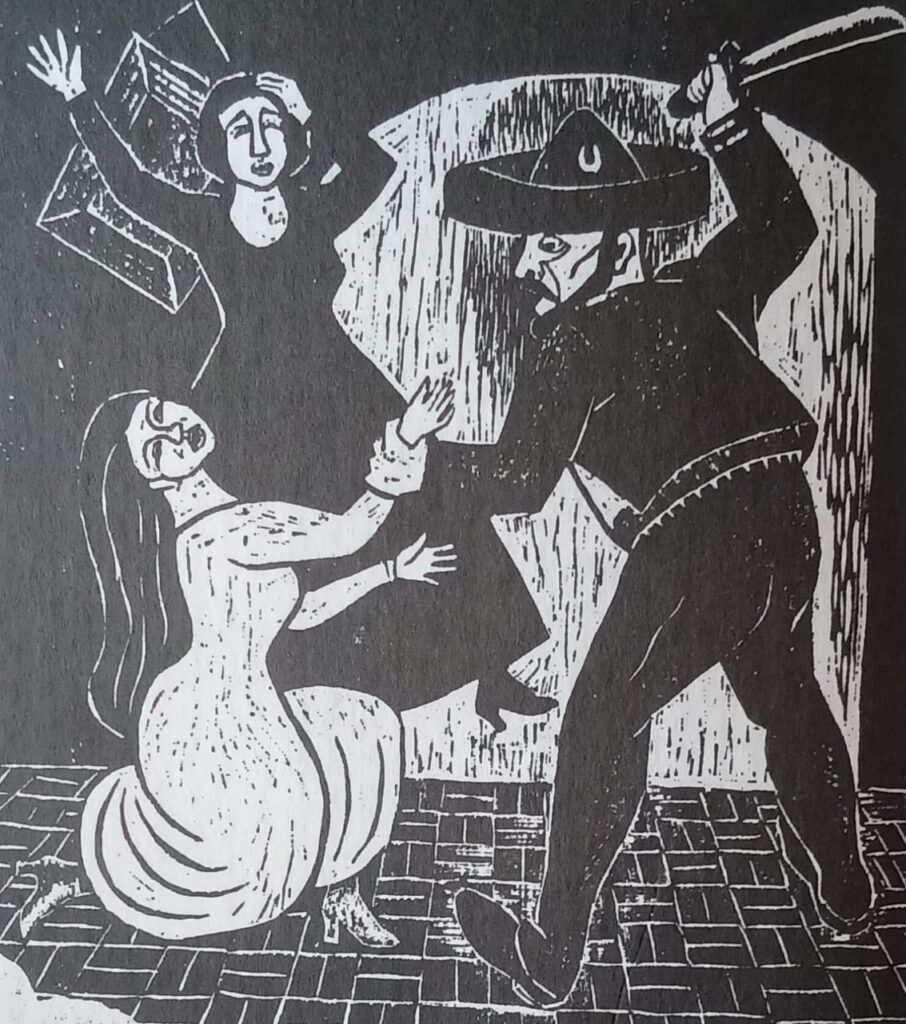

In this untitled work, which has also been called "Elena la traicionera", Isabel Villaseñor resorts once again to illustrating a corrido, this time of her own authorship. To represent the situation of women, the author resorted to the corrido genre; she wrote the lyrics, a theatrical piece and this engraving. In the corrido Elena speakinga young woman from the highlands of Jalisco in 1870, is courted by Don Fernando, a French military man. When her husband finds out, he kills them in separate events. In the image we can see Elena just before her partner murders her with a machete, while the domestic worker watches the scene in horror. Isabel Villaseñor in her work sought to represent many everyday situations of women: motherhood, care, self-representation and, in these cases, violence. By denouncing it both in her music and in her graphic work, she appeals to women's freedom over their lives and bodies.

Frida Kahlo (1907-1954)

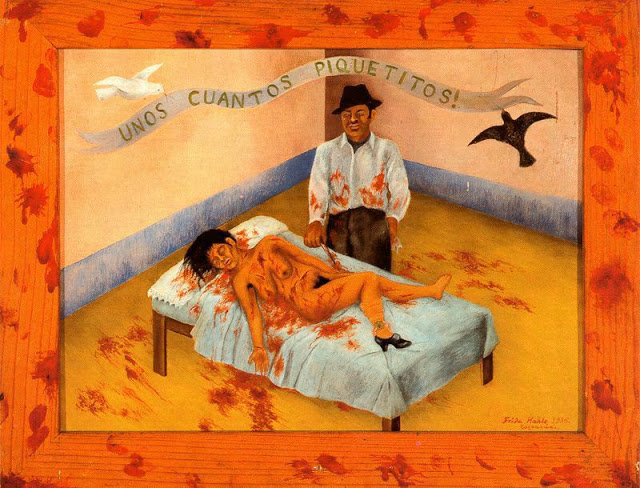

The artist apparently read in the newspaper that a man had killed his wife and in court she defended herself by saying that she had only given him "a few piquetitos". According to the police, there were twenty stab wounds. There is no doubt that Kahlo was sensitive to this feminicide and hence the crudeness and cruelty with which she represents it, where the image goes beyond the canvas and reaches the painting.

The Aguilar family, from Ocotlán, Oaxaca, has turned numerous times to the representation of Frida Kahlo, but rarely with some of the cruder works, as is the case of A few small bites. In this work by Demetrio García Aguilar, the image is reproduced exactly as it is: the stab wounds, the murderer's face, the blood and the only shoe the victim is not stripped of.

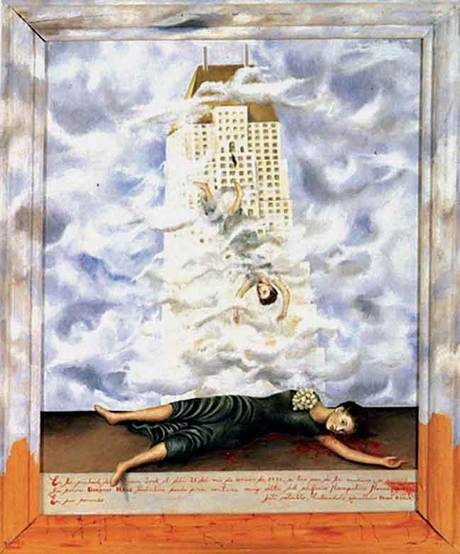

"In New York City on October 21, 1938, at six o'clock in the morning, Mrs. Dorothy Hale committed suicide by throwing herself from a very high window of the Hampshire House. In her memory [....] this altarpiece was executed by Frida Kahlo. (sic)"

Frida Kahlo she painted it when she was separated from Diego Rivera and apparently had suicidal thoughts herself. It has been said that it may be a visual commentary on the despair of women when a man abandons them. Dorothy Hale was an aspiring actress who, seeing that she had not achieved what she wanted, threw herself from her apartment in New York. It is said that she was commissioned to paint a posthumous portrait of Frida Kahlo, who depicted the exact moment of her suicide.

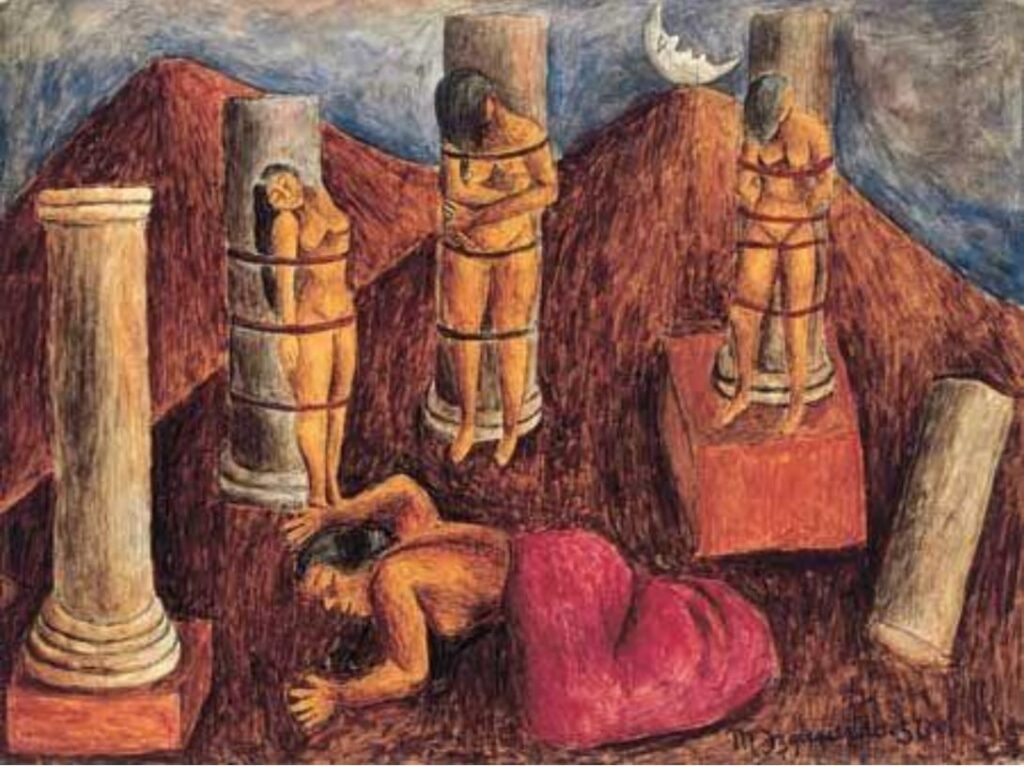

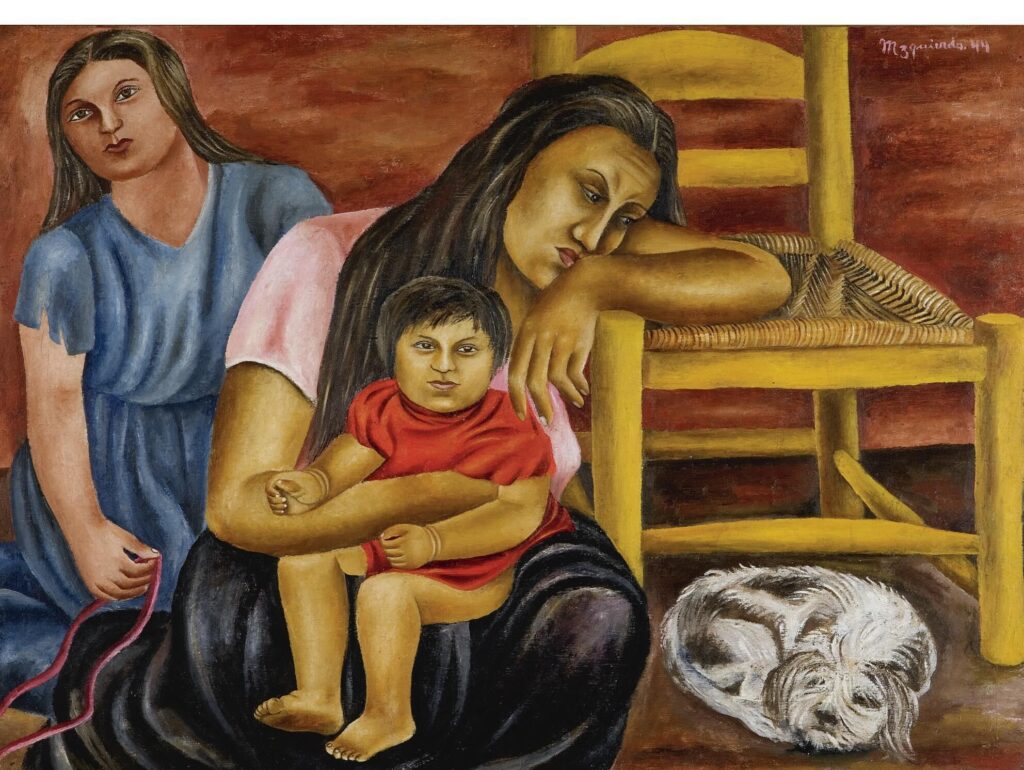

María Izquierdo (1907-1954)

It has been said that this work represents the pressure of women in patriarchy, specifically romantic love. Three naked women, tied to classical columns as a phallic representation in the midst of lifeless, lifeless mountains, like the rest of Izquierdo's metaphysical work. One woman lies on the ground with her naked torso inert and her skirt folded into a pink heart; behind her is a broken column. María Izquierdo, like many of the artists of the time, suffered macho violence in many ways, being excluded from creative spaces and even stigmatized for being an artist and divorced.

In this work, María Izquierdo depicts a woman sitting on the floor with her eyes lost, resting her head on a chair; in her arms she carries a child while behind her stands her daughter holding a string. Although this painting could be considered within the current Indigenista predominant in the art of those years, the painter seems to criticize the condition of the poorest women, whose situation hardly improved after the Mexican Revolution.

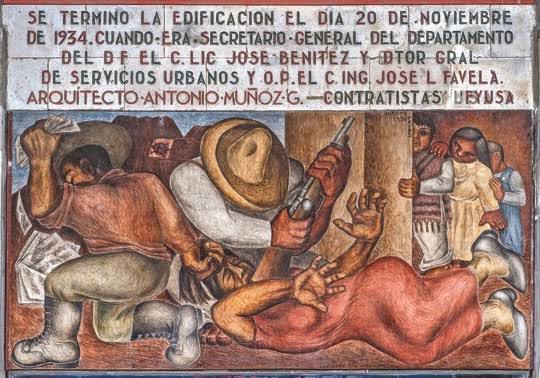

Aurora Reyes (1908-1985)

This was the first mural painted by a Mexican woman in a public building, the Centro Escolar Revolución located in downtown Mexico City. In it, Aurora Reyes depicts a woman brutally beaten: one man tortures her with a rifle while the second man pulls her by the hair with one hand and with the other pulls out a book; this second man with his body forms a swastika. It shows the brutal repression before the struggles of the teachers, always mostly female, especially in those years of the Cristero struggle that sought to abolish rural education as socialist. Behind a column, two boys and a girl observe the scene. Aurora Reyes was one of the painters with the greatest political participation and was an active member of the union of education workers.

It couldn't be more explicit. A burly man whips two naked women with a whip. One is on her back and the other is kneeling on the ground, while her face shows a gesture of pain and disgust with her eyes closed. Aurora Reyes, as part of her political activity, was also part of the feminist group "Las Pavorosas", so the theme of violence against women seems to be one of the concerns of her work.

Olga Costa (1913-1993)

In this work, Olga Costa shows us a still life that today has been considered part of the surrealist influence in Mexico. In it we can observe different elements that are distinguished for being dry and inert: from the skull of an animal in reminiscence of an animal, to the podsThe work is also made from the cactus, even parts of endemic plants, such as the pod of a capulín (a type of cactus). But the central object of this work is a dried cactus in the shape of a heart pierced by a knife. From the very title of the work, it seems to be a critique of love, with a traditional iconography: the knife as pain and the skull as the end of pleasure.

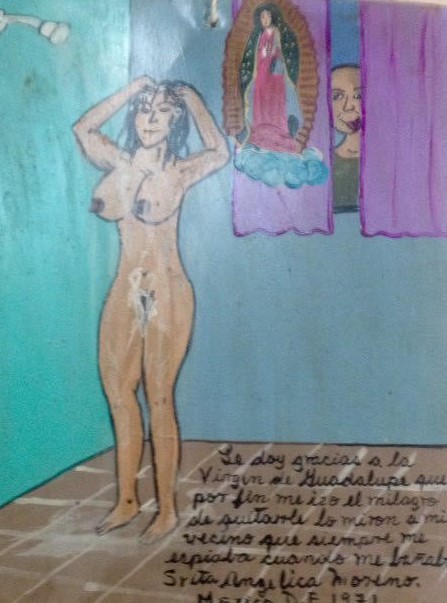

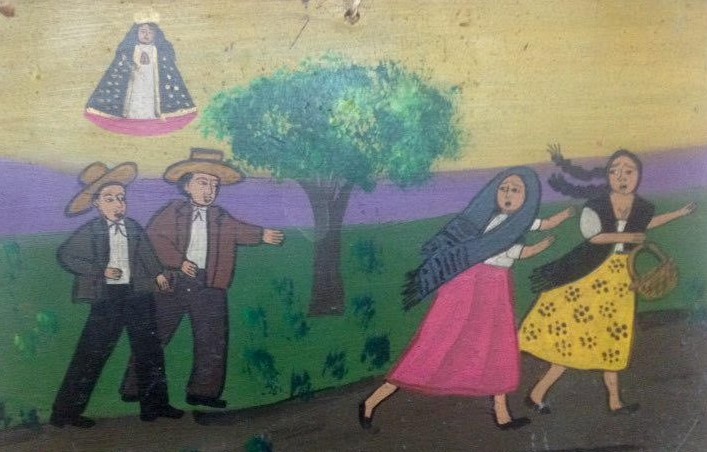

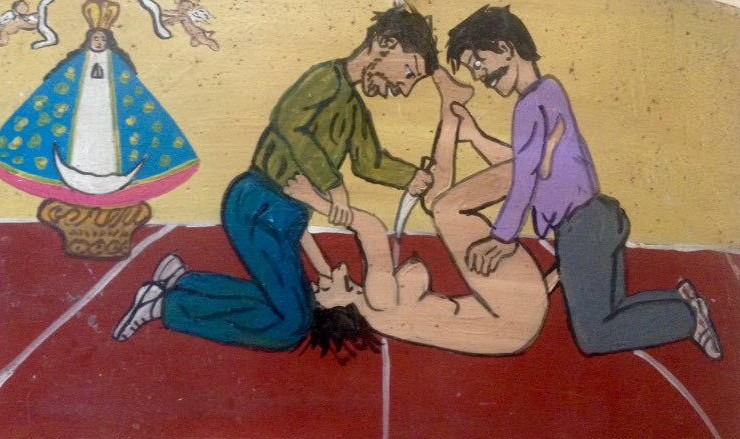

Exvotos

We are now going to refer to the painted votive offerings from Mexico, but it must be said that there are very few in which raped women appear. They are anonymous, therefore, we do not know who painted them but only the person who offers them, in this case, women. Two are supposedly from the 1970s and another from the 1950s. They may be real or invented, we don't know, but they are significant in terms of showing violence against women.

Some outsiders began to follow them with bad intentions, frightened ?we entrusted our honor? and in that moment, some ranch hands appeared and the outsiders got scared and left without ?attacking our virtue? 195?

She was assaulted, raped and thankfully didn't get pregnant. 1975

Sonia Felix Cherit (1961)

Visual artist, activist, feminist and director of Casa de Engracia de Zacatecas made a mural, The dress, 2020, for the virtual group exhibition The absent ones. The 43 participants expressed themselves against violence against women. The artist says: ?the work has an iconographic content that goes from romantic love, passion and abandonment to feminicide. The old existence of this evil that is violence against women reflected from mythology and since then remaining in impunity. The central figure of the dress -made of mud and blood- symbol of the abandonment of our dead women in dunghills, deserts and/or garbage dumps. Where many times it is the only garment of identification for their loved ones? This exhibition was presented on the occasion of the tenth anniversary of Casa de Engracia.

Adriana Raggi (1970)

Adriana Raggi. Self-representation. S/F.

Adriana Raggi. Self-representation. S/F.

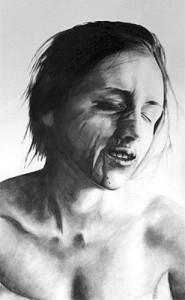

A face, presumably hers, all beaten up. A black eye and other signs of violence towards her. The same as in another drawing, which also shows a battered woman in her entirety.

Lapiztola Collective (2006)

Lapiztola emerged in 2006 when there was a strong conflict between the teachers' union and the Oaxaca state government. It is made up of Rosario Martínez, Roberto Vega and Yankel Balderas, who have dedicated themselves to urban art with stencil and silkscreen printing. At Let's sow dreams, let's harvest hopesLapiztola sought to pay homage to Bety Cariño, a defender of human rights, women and indigenous peoples, who was murdered in 2010 by a paramilitary group in the town of San Juan Copala. This work was painted on a wall in the center of the city of Oaxaca, whose government asked for it to be erased in 2015.

Black Sea (2019)

Mar Negro is a young illustrator and urban artist originally from Mexico City. She is part of PasteUp Morras, who are dedicated, as their name says, to creating urban art with paste up. Her work tries to denounce violence, feminicide and resignify sexual dissidence. In her work, female bodies are frequently present.

PasteUpMorras Collective (2020)

PasteUp Morras is a collective of women dedicated to urban art. They focus on denouncing harassment, violence and defending women's freedom. Their work is found both in Mexico City and in the State of Mexico, especially in areas where disappearances and femicides have occurred. Her work seeks to appropriate through art a space that is normally hostile to being a woman.

INSTALLATION AND PERFORMANCE

Elina Chauvet (1959)

Red shoesis an unequivocal installation that denounces feminicide in Ciudad Juárez, Chihuahua. This work has been presented in different places in Mexico and in about eight countries, perhaps approaching a hundred installations today. The artist herself stated that We have been living a pandemic of femicides for 30 years in Mexico?. The red shoes are recovered, symbol of imposed femininity, but also the pure shoes, immobile remains of women who are no longer there.

Maria Maria Acha-Kutscher (1968)

Transcultural and multicultural feminist artist. Sleeping beautiesThe performance is a project against male violence through the denunciation that involves many people in society from a broad call.

Sonia Félix Cherit (1961)

In 2020, Sonia Félix Cherit organized the exhibition "Las ausentes" at Casa Engracia, Zacatecas, as part of the Casa's 10th anniversary. In 2010 it was at the National Feminist Encounter, Zacatecas, but has been shown in several other places. No more violence against women" is the cry of this work. A huge red woman's body hangs in front of a canvas full of photos of women saying "No more violence against women". A pile of sand strewn with red body parts is in the center.

It covers many issues, sexual harassment, trafficking, organ trafficking and the femicide of girls, all referring to the violence that women suffer. A rich man carries a suitcase, The suitcaseThe scene of the murder, in which a dismembered girl is found.

In another suitcase he carries organs, in yet another suitcase all the evidence of the kidnapped and murdered girls. Throughout the performance, he exposes the explosive combination of narco-governments-rich people in power.

Natalia Eguiliz (1978)

An eloquent visual commentary on the mutilation and lack of freedom of women in housework symbolized by the pink apron, of course.

Katia Olalde

A beautiful black woman, with pink hair, in profile and carmine lips, wants to grab a multicolored butterfly, symbol of winged freedom.

PHOTOGRAPHY

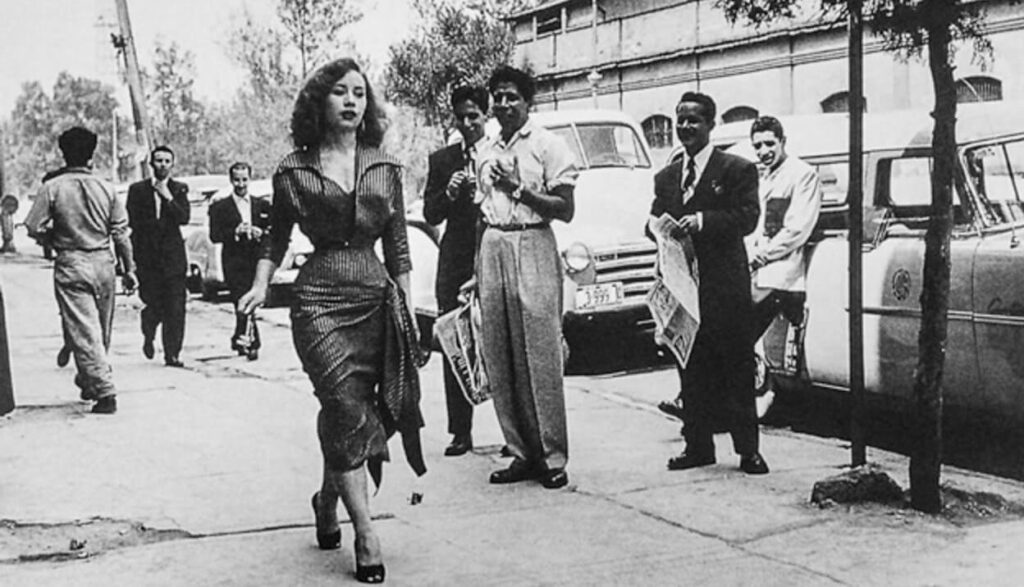

Nacho López (1923-1986)

A group of men throw compliments and looks at model and actress Maty Huitrón. This is a photo directed by the photographer, who told her friend Maty to walk around to provoke the compliments.

Lola Álvarez Bravo (1907-1993)

A woman leers out of an open window. The shadow of a gridded fence is on top of the whole photo. A metaphor, perhaps, of the confinement of this woman in her house. Lola Álvarez Bravo in some of her photographs and photocollages portrays women both in the domestic sphere and in their incursion into education and the labour market, always with a critical and, apparently, feminist gaze.

Rotmi Enciso (1962)

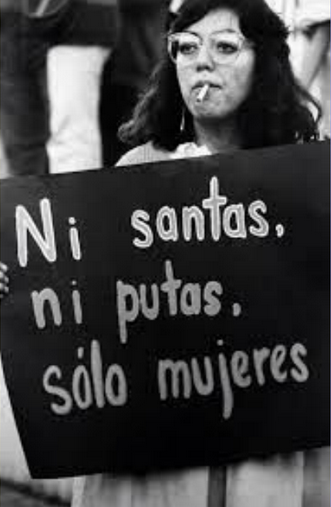

This photograph is iconic in Rotmi Enciso's work. It depicts a woman in the March 8 March 30 years ago.

Sonia Madrigal (1978)

Death comes out of the east is a work that addresses the issue of feminicidal violence in the state of Mexico and is based on three axes: documentary photography, territorial intervention and collective digital mapping. This work began in 2014 and is still in progress.

Daniela Edburg (1975)

Between reality and fiction. 2017.

What's left of the day. 2008.

What's left of the day. 2008.

Between reality and fictionn y What's left of the day are eminently clear projects about femicides in Mexico; in all three images women lie on the ground in the countryside. In the first one, the fiction is surely represented by the announcement of the bull while the crude reality is the woman lying. The other two make reference to the women murdered and sown as remains everywhere.

Monica Gonzalez (1976)

In Juchitán, Oaxaca, by tradition, the youngest daughter has to take care of her parents in their old age. Estrella represents economic security and companionship for her mother. Her father does not accept that she decided to be muxe. To be muxe is for the Zapotec population of the Central Valley in Juchitán, a pride. However, Estrella feels that there is a certain amount of rejection. In the last few years there has been a series of murders and aggressions against members of the homosexual community. Monica Gonzalez says, "Being a photojournalist on issues related to violence is not easy if you are a woman. She has a video project called ?Geography of Pain?

Romina Solís (1985)

This photograph is a simile of The Piropo, by Nacho López. However, this one is not directed as far as we know. It is the more than frequent response of men harassing young and beautiful women. We can even hear the whistles!

DOCUMENTARY FILMMAKING

Lucia Gaja (1974)

Five women from five countries tell their stories of domestic abuse: Finland, Spain, Mexico, India and the United States. It is important to see the coincidences between such different places and with such different economic development. Very different cultures, political and social realities converge in the same problem.

Tatiana Huezo (1972)

Two testimonies related to organized crime, prison in Mexico... and the ever-present disappeared.

Carolina Corral (1984)

This animated short is a visual story about women deprived of their freedom, who succumb to the all-too-frequent prison of marriage.

You may be interested in: Gun sales on the rise, domestic violence on the rise: experts