Forty years after the violent repression in Ayacucho, Peru's "corner of the dead," the military is once again leaving dead people in its streets. Time has passed, but the stigma has not.

By Ingrid Sanchez.

Photos: Miguel Gutierrez. Video: Candy Sotomayor

"Nobody here listens to us, nobody is going to listen to us."

This was the claim made by victims of military repression in Ayacucho, Peru, to the delegation of the Inter-American Commission on Human Rights (IACHR) that recently visited this department.

The reproach had the ring of pain rekindled by the military who, stomping hard, marched through Ayacucho once again. The last time they fired on the population was almost 40 years ago, during the internal armed conflict that left, according to the Truth and Reconciliation Commission, around 70 thousand dead.

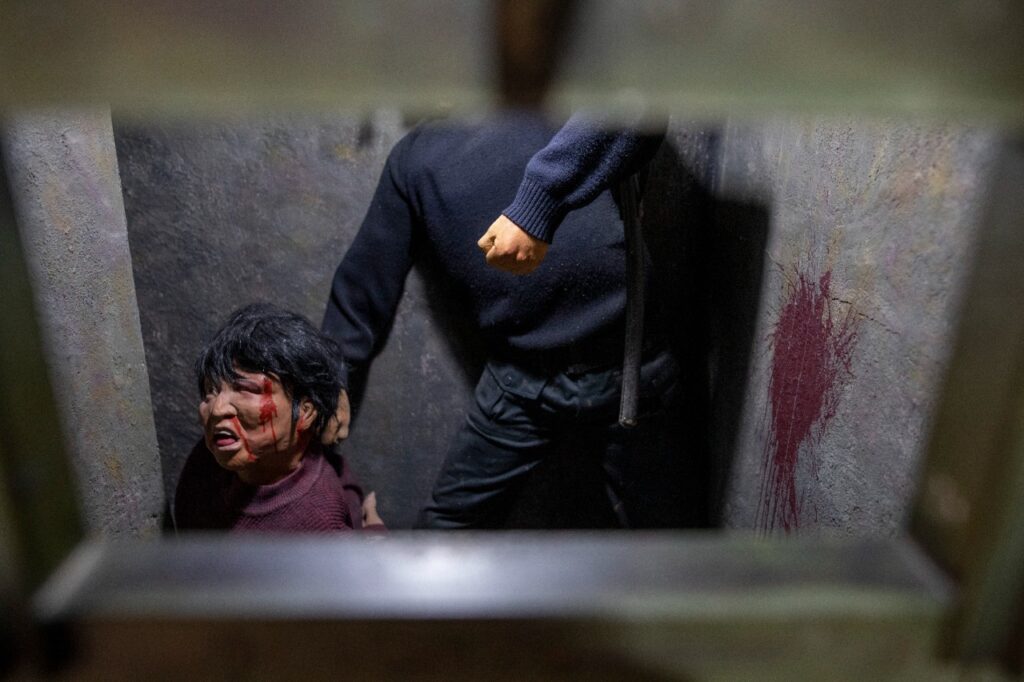

On December 15, the Army once again left streets covered with dead bodies in its wake.

At the meeting with the IACHR, it was reported that the dissolution of the social mobilizations at the end of December was extremely violent, with the use of weapons of war at will, shooting to kill, which reflects the violent death of the 10 victims and the large number of wounded.

The government of Dina Boluarte, who assumed the presidency on December 7 after the dismissal of Pedro Castillo, focused its repression on Ayacucho – "corner of the dead" in Quechua –; the contempt that had been dormant within the State against this region of the Andean highlands was reactivated after the relative calm that existed under Castillo Terrones.

Lima looks at Ayacucho with suspicion. People who migrate to the Peruvian capital from this region are not welcome.

For the people of Lima, they bear the stigma of “terrorists,” a label attached not only to those who served in the ranks of the Communist Party of Peru-Shining Path (PCP-SL), an organization banned from word to memory during the internal conflict. It extends to those who are “suspect” or originate from regions where the communists had influence.

On December 15, Ayacucho joined the strike called by several regions of the country demanding a Constituent Assembly to draft a new Constitution, and an end to the repression that has already occurred in southern Peru, such as Andahuaylas and Cusco.

The strike organizers asked the people of Ayacucho to take over the Alfredo Mendívil Duarte National Airport. They knew that from there the planes loaded with soldiers with bayonets fixed and heading south would leave.

The people of Ayacucho did not hesitate and took over the terminal. Hours later the State responded with all its force: for five hours bullets whistled in the Alfredo Medívil. After approximately 5:00 p.m., the persecution of the protesters began among the surrounding colonies.

The impacts of the bullets are the silent witness of the violence of the Boluarte government.

Where there were fallen people, the ground is a little cleaner than around it. The mourners washed away the blood of their husbands, sons, brothers, nephews or grandchildren with holy water.

Despite the bloodshed and the pain, the families will not remain silent and have formed the Association of Relatives of the Murdered and Wounded. They have begun the tortuous fight for justice.

Perhaps this historic combativeness and strength of the Ayacucho people is the reason that infuriates the economic and political elites, and the current State, to attack the region. It doesn't matter if it's the 19th, 20th or 21st century. The repression is the same.

"I found his clothes, "their little skulls"

«Then I found him. My husband disappeared on July 17, but I found him on August 15. But as I searched, I found his clothes, his skulls, his bones, what was left over from the dogs.»

The testimony is from "Mama Lidia" who speaks in front of her husband's holey shirt, kept in the Museum of Memory of Ayacucho; her story sounds current, but dates back to 1984, when her partner was murdered by the military.

"Mama Lidia" explains - as she sticks a finger into one of the holes in the last garment her husband wore - that she found his body abandoned in a river. She recalls that in addition to decomposition, his remains had perhaps been desecrated by dogs or local fauna.

With his strong Quechua accent, he says that Huamán was detained outside his home and then murdered for not carrying his National Identity Document (DNI).

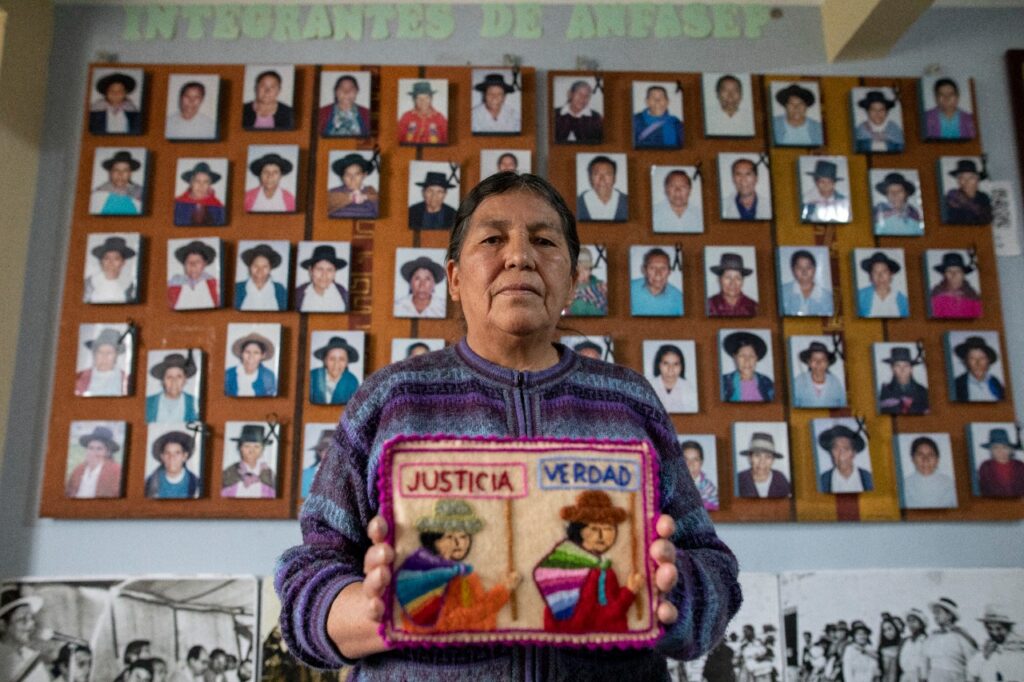

This woman, in her traditional dress, with her black hair braided and wiping away the tears that flow from her eyes at the memory of her husband, is the president of the National Association of Relatives of Kidnapped, Detained and Disappeared Persons of Peru (Anfasep), which since 1982 has focused on the recovery and identification of victims of violence in the internal armed conflict and justice for the families.

"They told me, 'There are dead people on this street. There are many dead people on this other street.' That's when I found my husband," Lidia explains, recalling the response of the authorities at the time.

The Ayacucho Prosecutor's Office refused to collect the body because "the judge is busy" so she returned to the river, collected the remains in a sheet and placed them on the judge's table with the claim of lack of assistance.

With the fortitude of his people, he took Huamán and buried him, after which he began his activism in Anfasep with the intention of finding the culprits.

Lidia is a case of "success" in the search for relatives, as she found the remains of her partner. Others have spent 40 years without hearing from their husbands, mothers, brothers or sons. Now, the violent repression of December 15 has opened several wounds among some members of the Association. The horror of the violence has brought back the pain of being victims.

Like that of Paula Aguilar, a woman who does not speak Spanish. In Quechua she explains that her mother and brother were disappeared by the Army in the 1980s and she has not found them. Now, her grandnephew was one of the 10 people killed by the military on December 15.

José Luis Aguilar was returning from work when he encountered a military pursuit in the neighborhoods surrounding the airport. He tried to hide, but a bullet hit him at a street intersection. He put his hand to his head and fainted; another young man dragged him to a sidewalk where he died.

"I feel sad, it's like I've relived that past year because at that time, the military killed and now it's the same. The military has killed. And that's why I relive what happened in the 80s."

Paula explains in her native language, Quechua. The linguistic distance of her testimony is no impediment to perceiving her pain in her tone and gestures.

Her main concern is the future of José Luis's two-year-old son. Paula stresses that in situations like this the State should provide financial compensation to the families of the victims of repression.

Ayacucho is one of the most marginalized regions in Peru.

To get to Paula's house, at one end of Huamanga, the capital of the department, you have to reach the last stop on a truck route and then climb for 25 minutes, over dirt and loose stones, to the top of the hill where she lives.

This marginalization led to the region being the epicenter of the PCP–SL's work since before the "People's War," the name the Party gave to the conflict that occurred between 1980 and 1990.

So, the Peruvian State, which from the comfortable center of Lima ignored Ayacucho, did not react to the first military actions of the Communist Party of Peru - the Shining Path in 1980. It was not until two years later that the Peruvian militia stood up to the Popular Guerrilla Army - the name given to its military organization by the Shining Path - and horror broke loose.

The internal conflict is not the only violent period that Ayacucho has witnessed. In 1824, the last battle against the Spanish took place, with whose share of blood and pain the independence of what is now Peru was sealed and the Viceroyalty of Peru was buried.

The Quechua-speaking population explains the meaning of the region's name: Aya means "dead" and k'uchu means "corner or dwelling." Ayacucho, whether in the independence struggle, in the two decades of "internal conflict" or in the uprising against Dina Boluarte, adds fallen to the "corner of the dead."

You can watch the video with interviews on the YouTube channel of Peninsula 360 Press.

This note was made with the support of the organization Global Exchange in collaboration with Peninsula 360 Press.

You may be interested in: Ayacucho: in the eye of the hurricane