SAN FRANCISCO, Calif. September 29, 2022.

With only a few days to go before October 2, the first round of Brazil's national elections to elect a president, Congress, governors and state legislatures, the country's democratic institutions are under great pressure.

Opposition candidate former President Inácio Lula da Silva leads by wide margins in virtually all polls, but current President Jair Bolsonaro has openly rejected the legitimacy of any possible outcome other than his re-election, mobilizing his supporters to do the same. Concerns that anti-democratic actions could trigger a return to military rule are widespread. Added to this are concerns about unfair electoral practices and even physical threats, especially against Black and Indigenous candidates, social activists and academics who have spoken out against increasingly authoritarian practices.

Global Exchange, an international human rights organization based in San Francisco, in collaboration with the communications team at Peninsula 360 Press, recently conducted a fact-finding mission to Brasilia and Rio de Janeiro, Brazil, to understand and document the socio-political conditions leading up to the elections.

The team was in Brasilia and Rio de Janeiro between August 30 and September 8, 2022. Numerous individual and collective interviews – focus groups – were conducted with ordinary Brazilians, as well as with journalists and renowned academics specializing in democracy, human rights, social justice and the environment.

In parallel, a team of data scientists from Peninsula 360 Press began analyzing the use of social media to spread false information and hate messages in the context of the Brazilian elections.

Electoral context

Elections will be held in Brazil on October 2. Not only is the country's presidency at stake, but also several elected offices: the vice presidency, state governors and vice governors, as well as part of the National Congress.

This electoral process has been accompanied by an intense political confrontation between the two main candidates: Luiz Inácio Lula da Silva, former president and left-wing candidate of the Workers' Party (PT); and the current president seeking re-election, Jair Bolsonaro, of the far-right Liberal Party.

In addition, there will be 11 other presidential candidates from different political parties representing a wide range of ideological and political leanings.

In Brazil, voting is compulsory for all citizens over the age of 18. In presidential elections, there is a first round and, if no candidate obtains 50%+1, a second final round.

This year's first round will be held on October 2. If no candidate wins a majority, the top two contenders will compete again on October 30.

Governors and vice-governors are also up for election, as is the Federal Senate. 81 senators representing one-third of the chamber will be on the ballot on October 2.

In the case of the members of the Chamber of Deputies, its 513 members will be elected and will have electoral candidates in 27 constituencies; likewise, the members of the legislative assemblies will be elected at the state level.

Incumbent President Jair Bolsonaro has consistently significantly underperformed his opponent Lula da Silva in polls throughout 2022. Due to the large field of candidates, a runoff election is likely; however, polls indicate that Brazil’s electorate is strongly inclined to bring back leftist former President Lula da Silva.

It is in this context that President Bolsonaro has amplified his unfounded complaints about the possibility of fraud in Brazil’s all-electronic electoral system. Many of the Brazilians we spoke to believe he is doing this to signal his intention to ignore election results if they do not favor him.

Results:

Environment and human rights

According to Dr. Celso Sánchez, a biologist and professor at the Federal University of Rio de Janeiro – UNIRIO –, the government of President Jair Bolsonaro has been characterized by unprecedented environmental devastation in Brazil, especially in the Amazon, considered the lung of the world; as well as a “significant increase in human rights violations.”

For this reason, according to Sánchez, director of GEAsur, UNIRIO's environmental studies laboratory, these elections are "absolutely important because the continuity of life is at risk not only in Brazil but throughout the world."

Sánchez points out that Brazil's 305 indigenous peoples, as well as Afro-descendant communities – known as quilombolas – have received some kind of "threat" from the current government. There are 6,000 quilombola territories in the country.

Brazil is not only a mega-biodiverse country, but it also has mega social diversity. What greatly threatened indigenous peoples and traditional native peoples was a subliminal incentive for paramilitary groups, illegal gold mining groups – interested in mining gold – to advance on indigenous territories, destroying their territories where, at the same time, there was a decrease in police operations, a dismantling of the Federal Police and the environmental control body.

Sánchez adds that President Bolsonaro's administration has also seriously neglected the massive wildfires in the Amazon over the past four years, which have had a global impact.

We had historic fires in very fragile and specific biomes, such as the Pantanal, which burned in unprecedented proportions, such as the Atlantic Forest biome, one of the hotspots of biodiversity on planet Earth… So it was a sequence of dramatic ecocide phenomena that have had a very visible influence on local climate changes, on microclimatologies, on the distribution patterns of winds and rainfall.

According to Sánchez, Bolsonaro's government has dismantled a satellite observation system for the Amazon, which now prevents accurate data on the ecological disaster from being obtained.

Political participation and violence

In response to the “ecogenocide,” as Sánchez calls the environmental devastation in Brazil, indigenous peoples have organized not only to resist, but also to re-exist through the creation of collectives, support networks, and minority candidates who will play an essential role in these elections. Added to this is the effort of artists, journalists, and academics who not only investigate ecogenocide, but denounce it.

These candidates “are predominantly female, black and indigenous. The role that black women have today, of course, given the gigantic legacy of Marielle Franco and the seed of hope that speaking in this seat of political occupation represents, the importance of black indigenous women, Afro-indigenous women… or as we prefer to call them: Afropindoramic… because pindorama was the name that our indigenous ancestors gave to the continent.”

Afro-indigenous youth also have a vast participation, they have organized the marches: the Margaritas march, the black women's march, the indigenous women's march; from here, many artistic leaders later emerged.

But the defense of land and human rights in Brazil can be very lethal. A recent case is the murder of the indigenist Bruno Pereira and the British journalist Dom Phillips, who disappeared on June 5, 2022 in the Yavari Valley. Regarding this murder, the newspaper Falha de S. Paulo wrote: “The tragedy exposes the Amazon as a lawless land sponsored by Bolsonaro.”

Sánchez says that Brazil is experiencing a “dramatic moment of violence.” Following the murder of black councilor Marielle Franco in Rio de Janeiro in 2018, many black women across the country followed her legacy of social activism; however, Sánchez denounces that political violence against these activists, and even against academics who work with them, has increased in the current electoral context: “Threats are received almost daily.” Sánchez himself has been threatened.

We are experiencing a dramatic situation of real and virtual threats, a complex situation because, for example, in the most affected areas of downtown Rio de Janeiro, we have the action of paramilitary groups that have already said – I witnessed it – that they would not allow people to vote for Lula in certain areas.

It is a very complex, challenging moment of growing hatred because what we see is a president who has a hate speech… he is imposing an increasingly hateful tone in his speech and I don't know how we are going to stop that, it is dramatic.

According to academics, Bolsonaro's speeches and actions keep the country at a very high level of tension that continues to increase as election day approaches.

Journalist Fernando Cruz explains that "while Bolsonaro continues to undermine the nation's democracy, Lula has made poverty and inequality a key prioritya message that resonates with many who remember the social achievements achieved during his previous term. Still, the country remains deeply divided, with growing fears of political violence on election day and concerns about the military’s position in the face of a potential crisis if Bolsonaro refuses to accept defeat. Many Brazilians still vividly remember the two decades of repressive military rule that ended in 1985.

This political division, as experts suggest, only creates more tension in the country, and we are seeing violent crimes emerging across Brazil.

Two months ago, on July 10, a agent killed local leader, Marcelo Arruda, treasurer of the Workers’ Party (PT) in Foz do Iguaçu. While Arruda was celebrating his 50th birthday, a prison officer, Jorge José da Rocha Guaranho, invaded the private party shouting “Here we are for Bolsonaro!” and shot Arruda dead. Arruda is survived by a wife and four children, including a baby.

In Finsocial, Goiânia, a 40-year-old business consultant named Davi Augusto de Souza was shot in the leg on August 31, 2022 by Military Police Corporal Vitor da Silva Lopes during a fight over politics in a church, according to Souza's family. As reported by the Correio Braziliense, Souza's brother's testimony claimed that the fight began with "a debate over whether church members should support the government or not, and that members should not vote for the left, as leaders indicated," he reported.

Just a few days later, a newspaper article The Country reported that a political argument led to a murder in a rural area of the state of Mato Grosso, in the interior of the country. According to data from the Civil Police, Rafael Silva de Oliveira, 24 years old and a supporter of President Jair Bolsonaro, stabbed to death Benedito Cardoso dos Santos, 44 years old and a supporter of Lula da Silva, after a heated argument about politics got out of control on September 7, 2022. The police have no doubts about the political motive of the murder.

The 2022 election campaign has accumulated episodes of violence against candidates and supporters of left-wing parties. The candidate for federal deputy Vanessa Negrini, of the Workers' Party, and her supporters were threatened twice in the same day, in Guaráon September 11, 2022.

André Borges, a political scientist at the University of Brasilia, believes that the elections in Brazil are important because, although there is little chance of a coup, there is a high probability of political violence similar to that which occurred in the United States when Donald Trump's supporters stormed the Capitol.

"People agree that the likelihood of a coup is very low, it's very unlikely that we're going to have a break with democracy, but I think there is a concern that there could be some kind of political violence, some kind of repeat of what happened in the United States after the last election when supporters of the former president invaded the Capitol, we have that concern."

However, although there is skepticism about a coup, the population lives in fear of expressing their political ideas due to the increasingly frequent attacks by Jair Bolsonaro's supporters on anyone who shows their support for Lula.

According to the study "Violence and Democracy: Pre-election Panorama Brazil 2022", published on September 17, seven out of ten people say they are afraid of being physically attacked for their political opinions.

The Datafolha research institute surveyed 2,100 people aged 16 and over across the country between 3 and 13 August.

67.51% of respondents said they were afraid of being attacked and 3.21% said they had been threatened for political reasons in the last month, which is equivalent to 5.3 million Brazilians.

The document also lists a series of attacks that Lula's supporters have suffered in recent weeks, including murders at the hands of Bolsonaro's police, attacks with feces on Lula supporters, and more.

These violent acts become more relevant as the election date approaches.

Bolsonaro's anti-democratic narrative

The possibility of Bolsonaro winning the election cannot be ruled out, says Dr. Adrian Albala, a professor at the Institute of Political Sciences in Brasilia; however, opinion polls indicate that the president is set to lose the election and is therefore constructing a narrative of fraud that, if Bolsonaro loses, could trigger violence from his supporters, many of whom are military, police and even armed civilians.

Bolsonaro's narrative throughout the election has been anti-democratic, claiming that the electoral system cannot be trusted and that he believes there may be fraud in Brazil.

"However, it must be remembered that the current president – Bolsonaro – and his children were elected through the same democratic system that he criticises today," explains Carolina Botelho, a political scientist at UERJ.

Botelho, who is a professor and researcher at the Mackenzie/Cognitive and Social Neuroscience Lab and an associate at the Electoral Studies Lab, explains that “when people validate Bolsonaro’s intentions, his anti-democratic narrative, and the electoral dynamics he’s trying to put in place, we can see that this has more to do with creating a solution for him if he loses the election. So far, there’s no evidence of fraud in the election. What we do have evidence of, so far, is that this president’s chances of reelection are very low and have gotten worse over time.”

Political communication and public opinion expert Botelho says that “one way Bolsonaro could resolve future election results is by discrediting the electoral system. Even though the electoral justice system has responded firmly to his accusations and has shown the population – who already understands and knows their democratic system – that fraud is not possible and that Bolsonaro’s anti-democratic narrative is an attempt to gain some political advantage in case of his defeat.”

Cruz, for his part, writes that “for Bolsonaro, the threat from Alexandre De Moraes [Brazilian jurist, recently appointed president of the Superior Electoral Tribunal and justice of the Supreme Federal Court] comes in part from his focus on online political disinformation, which has been a key tool for Bolsonaro throughout his presidency, allowing him to shape the message on a range of issues, from COVID-19 vaccines, to Amazon deforestation, and of course, the upcoming elections.”

In technical terms, André Borges explains that elections in Brazil are centralized and operate with an electronic voting system that, on the one hand, guarantees that all states have the same vote counting system supervised by the Superior Electoral Court and, on the other, allows for fewer errors when counting votes.

In addition, specialized hackers have been asked questions and tested to see if it would be possible to hack the electoral system, and they have explained that it would not be possible.

"There is no element that points to the possibility of fraud, in reality this is just a narrative that they are creating because in the end Bolsonaro and some military personnel are connected to Bolsonaro and to the extreme right in Brazil, they do not want to accept the result in case they are defeated."

Another element that has played against Bolsonaro was his response to the COVID-19 pandemic, especially his constant statements in which he underestimated the pandemic by considering the disease as a simple flu. In addition, vaccination in Brazil was slow compared to other countries in the region such as Chile.

But, according to Borges, the reason why Bolsonaro could probably lose the election is mainly related to the economy.

«Why is Bolsonaro going to lose the elections? It's because of the economy. That's why Lula, from the Workers' Party, is much better among poor people, because they have those memories of his government, of Lula's government when inflation was low and the economy was growing, and they compare it with what is happening now.»

But, according to Borges, the reason why Bolsonaro could probably lose the election is mainly related to the economy.

Bolsonaro's anti-democratic discourse on social media

During the 2022 Brazilian elections, we have seen a re-edition of Jair Bolsonaro's dangerous anti-democratic discourse. This is crystallized in different expressions, often under an apparent democratic veil; Bolsonaro's discourse remains authoritarian and refuses to accept horizontality as a democratic ideal.

Bolsonaro has spread an anti-democratic message through social media. Since his first candidacy, he has based the dissemination of his messages on social media. It is therefore through them that we can identify those meanings where his ideological position is consolidated, which, in turn, allows us to follow the voice of his followers. In this report, we will only touch on two elements: the struggles for gender equality and Bolsonaro's claim to environmental resources for "development".

• Combating struggles for equality for gender dissidents. Bolsonaro's discourse has combated any expression that allows for the inclusion of gender dissidents, a situation that we can identify in his categorical rejection of inclusive language.

An example of this was during Bolsonaro's speech in Brasilia during the bicentennial parade, where he called on his followers to show "virility" and find a "little woman" to accompany them in their lives.

Their "pro-family" position is declared against homoparental families. Their discourse condemns both dissent and family configurations that do not adhere to the "traditional family." Both break with the democratic notion of the inclusion of different social forms, since they start from a hierarchy of values where the "superiors" can impose their ways of life on the "inferiors."

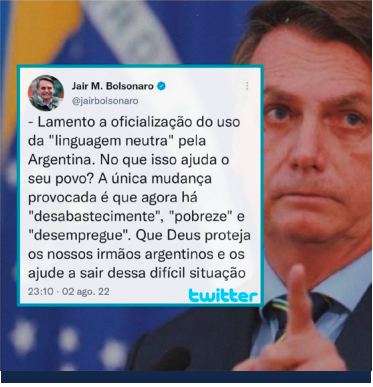

In the first capture (figure 1) we found Bolsonaro's message from his Instagram account –with 21.3 million followers– where he condemns the officialization of inclusive or neutral language in Argentina.

This adds a risk condition to his "Argentine brothers" whom he entrusts to God. Two central elements in this piece consist of the condemnation of language that gives voice to gender-sex dissidence, which contrasts with his entrustment to God and, therefore, is linked to religious movements that also reject this transformation of language.

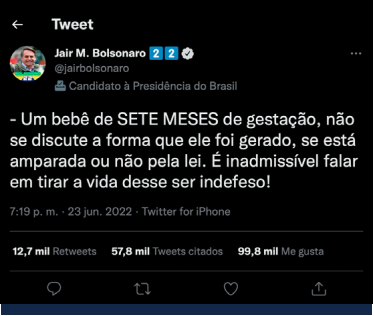

A second message, which also appeals to the support of more religious voters, consists of his support for the traditional family.

Contrary to feminist demands, in which the movement seeks freedom in reproductive choices, the candidate's position rejects women's right to terminate a pregnancy, assuming as its own the condemnation made by religious groups.

Bolsonaro is shown in this video (Figure 3) reaching out to a baby in the middle of the crowd and holding him up for everyone to see. The video is accompanied by the music “The Circle of Life” from the soundtrack of Disney’s “The Lion King.”

The Figure 2 This is a screenshot from Bolsonaro's Twitter account, which says: "A baby who is seven months pregnant, it is not a question of discussing the way in which it was conceived, whether it is supported by the law or not. It is unacceptable to talk about taking the life of this defenseless being!"

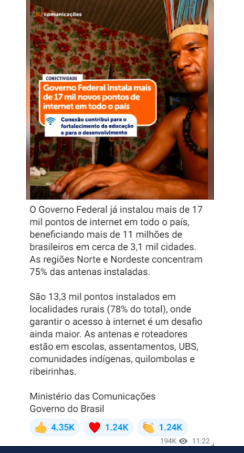

-Developmentalism. The Bolsonaro government seeks to “develop” the Amazon by transforming it into a space of capitalist exploitation. For the same reason, there is a vision of the native population as “backward” and opposed to progress and development. This idea presents the indigenous population as one that “needs” to be transformed in order to be included within the capitalist vortex, thus finding an imperial view where there is no respect for other forms of life. In this way, the “developmentalist” imposition hides the destruction of the other. For the same reason, there is no democratic vision of the native populations.

The Figure 4 – published on Jair Bolsonaro’s official Telegram account – shows the native population as eager for progress. Where the headdress and traditional clothing contrast with the possibilities represented by the connection to the world of social digital networks. This apparent benefit is an imposition of a type of society without giving voice to the native communities. Therefore, this image is built around the contrast between development and backwardness.

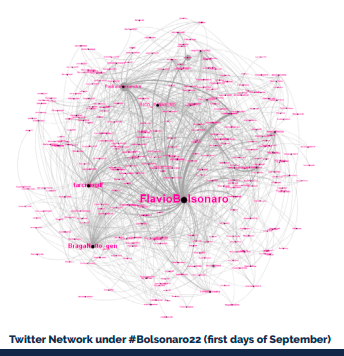

President Bolsonaro's messages only come from his narrative. Their impact spreads from a series of dominant nodes in the different social-digital networks that seek – through high-impact opinions – to dominate the conversation. Therefore, there is no logic of dialogue, but rather manipulation is sought to attack the adversary. On the Twitter platform, some stand out: i) Flavio Bolsonaro (@flaviobolsonaro), son of the president, who from his position as senator of the republic is one of the most prominent nodes of the Bolsonaro clan. A character accused in the media for his extravagant expenses; ii) Braga Netto (@braganotto_gen), former military man and vice-presidential candidate. A conservative user with deep ties to the Brazilian military elite; iii) Tarcísio Gomes de Freitas (@tarcisiogdf), candidate for the government of São Paulo and who also advocates the rejection of the rights of gender dissidence; iv) Rico Pinheiro (@ric0_pinheir0), a Brazilian businessman who promotes a development policy based on the actions of private companies; and Alexandre Padrao (@PadraoeAlexandre. ), an anti-PT activist on social-digital networks.

The elections in Brazil pose a reissue of Bolsonaro’s political proposals. He proposes to continue with a liberal model of development – now under the protection of traditional ideas – that seeks to continue the unlimited exploitation of bodies and the forest from an anti-democratic imperial position that does not consider other forms of life and, on the contrary, seeks to impose – often from social-digital networks – a model of destruction and discrimination towards different minorities. Therefore, from a critical point of view, we must condemn these positions that, under a cloak of democracy, seek to legitimize the exclusion of others.

Global Exchange's coverage of Brazil's elections

Global Exchange will provide coverage of the Brazilian elections, both in the first round on October 2, 2022, and in the final round on October 30, 2022.

Our team, made up of international and local journalists spread across Brasilia, Rio de Janeiro, São Paulo, Salvador de Bahia and the Amazon, will produce reports and multimedia content in English and Spanish that media outlets interested in the material can publish on their platforms.

This work is carried out in collaboration with Península 360 Press, Rompeviento TV, Ethnic Media Services, Brasil de Fato and Peoples Dispatch, Levante Popular da Juventude and Movimento Brasil Popular.

You may be interested in: What is at stake in Brazil on October 2?