By Katarina Machmer. Ethnic Media Services.

Editor's note: War, famine and climate change are once again causing a surge in migrants seeking entry into the European Union, which is legally required to assess asylum cases before expulsion. In EU member nation Croatia, however, an ongoing policy of illegal and sometimes violent pushbacks has human rights groups sounding the alarm.

ZAGREB, Croatia – One of the European Union’s longest borders stretches across hundreds of miles of deep forest separating EU member nation Croatia on one side and Bosnia and Herzegovina on the other. For any EU citizen, the scenery is breathtaking.

But for migrants and refugees trying to enter the EU, “the jungle”, as many call it, can be both a blessing and a curse.

“We hide in the forest on the way to the border, but there are many difficulties along the way, such as snakes and the danger of getting lost in the dark of night,” says Amar – not his real name – who is originally from India. Unexploded ordnance and landmines, remnants of the 1992-1995 Bosnian War, add to the risks faced by migrants.

Irregular migration into the EU – refugees and migrants entering the bloc without documentation – is rising sharply, approaching numbers not seen since 2016, when estimates reached 1.6 million, according to the EU’s border agency Frontex. War, famine and climate change are among the drivers of this latest surge.

Most arrive along the so-called “Balkan route,” which runs northwest from Turkey, through Greece and into the Balkan nations that form the southern border of the 27-member EU. In 2015, the route became a key artery for migrants from the Middle East and Africa. But after Croatia, Slovenia and Serbia closed their borders, Bosnia and Herzegovina emerged as the region’s most important transit country.

Some 87,000 migrants have arrived in the country since 2018. The increase comes as renewed tensions stemming from the 1992 Bosnian War are beginning to resurface.

“Ten times in a row.” That’s how many times Amar has tried to cross, and each time, “the police caught me,” he says. Another migrant, from Iran, says he has made more than 200 attempts.

Amar lives in Camp Lipa, a Temporary Reception Centre (TRC), or migrant camp, in the northwestern corner of Bosnia and Herzegovina that opened last year after the country came under fire for its treatment of migrants. The camp is a few days’ walk from the Croatian border, along rugged terrain that, while closely monitored, also provides opportunities for migrants to fly under the radar.

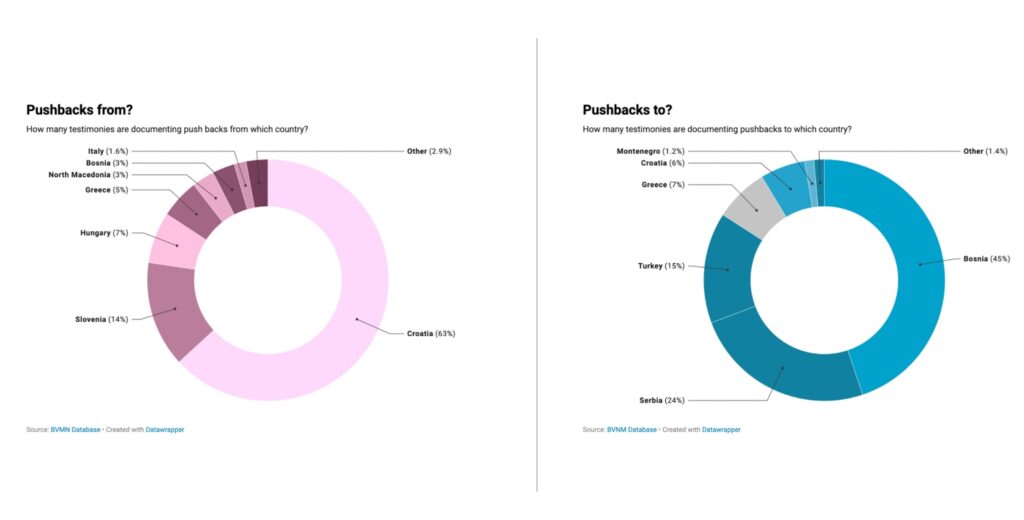

Still, reports show that Croatia, along with neighbouring Greece and Romania, has carried out hundreds of illegal pushback operations, forcing migrants like Amar back across the border. In one documented case from 2020, Croatian authorities forcibly expelled more than 2,000 migrants in a span of 19 days.

The operations have raised alarm bells among human rights groups who say the EU is complicit. EU and international law requires member countries to first assess an asylum seeker's case, including irregular border crossings, before expelling them, a principle known as non-refoulement.

Croatian journalist Yasmin Klarić has covered the pushback operations and says they are part of Croatia's efforts to become part of the Schengen Area, made up of 26 EU countries that have abolished virtually all border controls. Croatia's entry into the zone would allow its citizens to travel freely across EU member countries.

Klarić believes that pushback operations are becoming increasingly normalised and that the EU has no interest in ending them. On the contrary. “If the EU brings Croatia into Schengen, it will not do so despite the fact that the country is hitting migrants and refugees, but because it is doing so,” says Klarić, pointing to a general shift in EU policy towards deterrence along its borders.

That shift can be seen in the support given by the European Commission, the EU’s executive arm, to Croatian border police, as well as in the statements of leaders including Ognian Zlatev, who represents the European Commission in Croatia. “If people try to cross the border irregularly,” he says flatly, “this is a crime.”

Meanwhile, with a global food crisis exacerbated by the war in Ukraine and simmering conflicts in Africa and the Middle East, the flow of migrants continues, fuelling an ongoing humanitarian crisis along the EU's southern border.

“The border police did that,” says one Camp Lipa resident, pointing to an injured arm. “You journalists come and report to us all the time, but nothing changes,” complains another.

Arnela Čauŝević works at a TRC in the village of Uŝivak, near Sarajevo, the capital of Bosnia. She says that despite the obstacles to entering the EU, few migrants opt for asylum in her country. “I only know two or three who tried to apply for asylum in Bosnia. The others continue to cross the border, even if they need 100 times to succeed.”

The Uŝivak camp is home to mostly families, housed in containers built on ground parched by the summer heat. One family from Pakistan is already preparing to cross the border just days after their arrival following a 15-day trek from Serbia with little food or water and a sick daughter in tow. Their goal is to reach Germany.

Another family that fled Afghanistan after the Taliban returned to power there is also preparing to try their luck at the border. "If we don't manage to cross," says the father, "we'll try again."

Katarina Machmer is a Munich-based journalist covering migration and politics.

You may be interested in: Heat, the main threat to agricultural workers: Stanford specialists