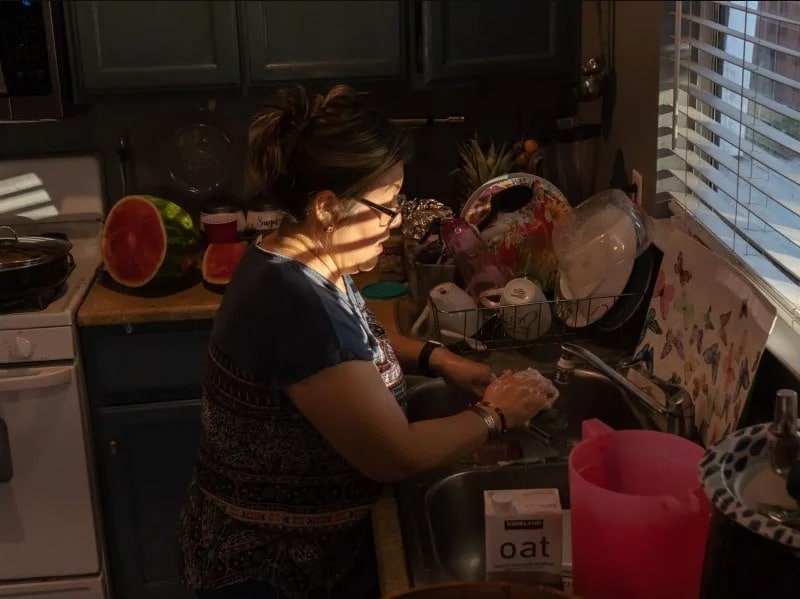

Pictured: Ignacio Yepez listens to interpreter Rosa Cardenas through an audio transmitter during a special meeting of the Lodi City Council at the Loel Senior Center in Lodi, California, on March 29, 2023. The meeting was called to fill a vacant seat in the 4th District, following the resignation of Shakir Khan. (Harika Maddala/Bay City News/Catchlight Local)

This article is part of “More Than Words,” an initiative by Report for America that brought together newsrooms covering Latino communities in eight states to examine the impact of language barriers on the economic, social and educational advancement of Latinos and local efforts to remedy this situation.

By Victoria Franco, Bay City News Foundation.

In February, Griselda Juarez left work early at Premier Finishings, a company that specializes in painting auto parts for various automakers, and rushed to prepare a meal for her family so she could attend a quarterly community meeting with the Stockton Police Department.

Juarez, 50, of Weston Ranch in Stockton, never misses a single one of these meetings, hoping to get a response to a request for more grocery stores in the area and to discuss crime and safety issues in his neighborhood. But more often than not, he returns home without having been able to voice his concerns.

Juarez does not speak English and there are often no translation services available to understand what information is being shared and to allow him to ask questions.

“At the last meeting we had with the police, the officer said there was no one to interpret, no one to help us, so I got nothing out of it,” Juarez said. “I felt like I wasted my time… I went to sit and warm the seat, as people say,” he added.

Nearly 45 percent of Stockton residents are Latino, and nearly 40 percent of people living in San Joaquin County speak a language other than English at home, according to the census. Many who only speak Spanish, like Juarez, are frustrated that language barriers prevent them from getting public safety information.

Now, they are calling on city officials to step in, offer solutions and create a real connection with Spanish speakers in the area.

The problems extend beyond meetings. Residents point to a lack of communication and support in their language as a major obstacle to building trust between the community and police, which increases the risk of limiting public safety information for an already vulnerable population and reducing opportunities for them to contribute to community improvement and increase their representation at all levels.

A killer on the loose, a gap in communication

Last October, the potentially dangerous consequences of the language barrier were on display when Stockton officials held a town hall meeting to discuss the danger posed by a series of murders that had been occurring in the city since April 2021. At that time, seven people had been killed or injured by gunfire. Five of them were Hispanic men.

During the meeting, city officials told community members about the killings, sharing tips on how to stay safe, especially in the early morning hours. However, several Spanish speakers present that day left the meeting disappointed and frustrated because they were left out of the conversation after translation services failed.

This was particularly worrying for the farm workers present, who are some of the most vulnerable, as they leave for work in the morning, before dawn and often alone.

"Remember our people who work in the fields. What time do they get up?" said Luz Sauceda, a health educator from the council, a non-profit organization that offers a multitude of services, primarily to the Hispanic population of the Central Valley.

Mayor Kevin Lincoln said after the meeting that another meeting was held specifically for the Spanish-speaking community and that he invited other community members as well.

“I hear you, your city hears you,” Lincoln said in English, responding to those who felt excluded. “We are here to serve you and do the best we can to meet you where you are, at the point of your needs.”

Translation challenges

Stockton police say when they organize a meeting they rely on members of the Chief's Community Advisory Board, a group created in 2012 to improve communication between Stockton residents and police, to help translate for these meetings.

But at the quarterly meeting on Feb. 14 there was no one to translate.

Juarez and Ernestina Barrios, another Stockton resident, said Zoyla Moreno, a Weston Ranch neighborhood watch captain, has tried to translate for them.

However, that has only created a more stressful environment for them.

Dialogue is good, forums are good, but work has to be done beforehand and people's trust has to be developed.

Luis Magana,

A farmworker rights advocate in the Central Valley

Their complaints focused on the quality of the translation and the lack of headphones to listen to it.

Barrios says that at one particular meeting, an English speaker said they couldn't hear what was being said or pay attention because of the translation going on right next to them, which made Barrios feel uncomfortable.

“I think that’s the problem,” Barrios said. “Because the woman is translating, but she’s not going to be right next to me, right? Instead she has to speak louder, she can’t whisper in my ear. So, I think, it interrupts the hearing of the people who are close to me.”

He added that it was difficult for Moreno to interpret during the meeting because he also had to pay attention to what was being said.

Although Moreno offered to translate for the two women, she is not certified as a translator, nor does she have the necessary qualifications to translate during the meetings.

Both women say they would like to see the Stockton Police Department return to using earpieces that were previously used to allow Spanish speakers to hear a translation of meetings.

Stockton Police Department spokesman Joseph Silva said in March that the department had recently purchased headsets that would be used at upcoming meetings.

In the adjacent city of Lodi, Stockton, hearing aids were helpful in overcoming language problems during meetings and hearings.

Rosa Trevizo, a California-certified court interpreter, attends every city council meeting to make sure Spanish speakers understand what is going on by helping them speak during public comment periods.

She says she has worked as a translator for the city for eight years, attending meetings even if people have not requested the service in advance.

At a special city council meeting in March, Trevizo gave more than 20 people headphones through which they could hear his translation during the more than three-hour meeting, which discussed who would be selected to fill a vacancy in the 4th Ward on Lodi’s east side after a council member was accused of voter fraud.

Members of the Hispanic community who were upset about potential voter fraud and wanted a voice in the decision were able to address the council with Trevizo's help.

The City of Stockton also said it is working on other alternatives to help its residents, including a website that will offer a translation option through Google services and a translation service through Amazon, which will give residents bilingual options to access information and updates on the site.

Beyond translation

Despite the translation of these sites, Barrios says she feels that more meetings should be held in Spanish or with translation services.

"I don't think it's fair, I want the voice of Latinos to count, the voice of one as a Hispanic," he said.

Spanish speakers in the community believe another way to begin bridging the gap is for city officials and police to connect with the community to build trust.

"Dialogue is good, forums are good, but you have to do the work beforehand and build people's trust," said Luis Magaña, a farmworker rights advocate in the Central Valley.

Magaña has already seen the benefits of this strategy. He recalls a former police chief in San Joaquin County who did not speak Spanish but made inroads with the Hispanic community by showing he cared about the problems they faced.

For Magaña, knowing that authorities care enough to reach out and engage with the community, even if they don't speak the language, can open many doors.

I don't think it's fair, I want the voice of Latinos to count, the voice of one as a Hispanic.

Ernestina Barrios,

Stockton resident

"He spoke to us and Spanish is not necessary when people can feel the trust and willingness," he said.

Magaña said that while some city officials do communicate with the community, he feels it needs to happen on an ongoing basis and would like to see more follow-up from city leaders.

Juarez said that although she and her Latino community continue to face language barriers in matters of public safety, she will continue to attend every meeting with police because she wants them to know that Spanish speakers matter and deserve representation, in the hopes that increased visibility will lead to lasting change.

“I think that even if we don’t understand (we should go), so that they see us and see that people are interested,” Juarez said. “…a lot of people don’t go to the meetings and I tell them ‘we have to go, even if we don’t understand, they have to see us, make them see that we are interested, that we want to change our neighborhood and do new things.’”

This article was translated into Spanish thanks to RFA. You can read the English version here.

You may be interested in: The battle to ban books in schools sharply escalates