By Pilar Marrero. Ethnic Media Services.

Throughout Latin America, writers who once relied on magical realism to capture the region's realities are increasingly turning to science fiction and fantasy.

For countries in the Global North, the term polycrisis has become something of a dark cloud over the horizon. The concept is increasingly the stuff of dystopian fantasies about a future in flames due to the convergence of multiple global and existential challenges.

In Latin America, the polycrisis has defined much of its history, and where writers once turned to magical realism, many are increasingly turning to science fiction to describe that reality.

Speculative, fantasy or imaginative literature – in other latitudes called science fiction – has a series of young representatives throughout Latin America who write to explore, from a different point of view, the harshest and most difficult realities of a continent accustomed to crises, poverty and corruption.

“A very common mistake is to confuse what we are doing in Latin America in terms of non-mimetic literature with magical realism,” explains, not without a hint of irritation, Mexican writer and editor Libia Brenda. “Many in the North think that if it is not the science fiction they know, then it must be magical realism.”

What writers like Alberto Quimal and Gabriela Damián Miravete (Mexico), Fernanda Trías and Mariana Enríquez (Argentina), Ignatio de Loyola Brandao (Brazil), or Liliana Colanzi and Edmundo Paz Soldan (Bolivia) are doing as literature today, has little to do with what Gabriel García Márquez, the greatest exponent of Latin American magical realism, did.

Writers like García Márquez, whose most emblematic novel, One Hundred Years of Solitude, takes place in the fictional town of Macondo, always said that their literature was imbued with their reality, lives, stories, past, with the magical and extraordinary element that is not explained or commented on, it only exists in a natural form. In contrast, the current boom in Latin American literature delves into themes as varied as horror and environmentalism, technology, dystopia and fantasy.

According to some observers, these new works focus less on reconciling the past than on making sense of a tense and uncertain future.

[embedyt] https://www.youtube.com/watch?v=zlVT-JAI4OA[/embedyt]

"The region is finding in its literature the futures that its politicians are unable to imagine," writes writer Jorge Carrión in an essay in the New York Times. The title of the essay is "Latin American Literature Takes a Turn Toward the Future."

In other words, Brenda says, “we do our own thing here.”

A “fantastic literature of another order”

This speculative literature, also known in other circles as "science fiction" - although this term is used more in the English-speaking world than in the Spanish-speaking world, at least to define what is done locally - is also quite different from what is done in the English-speaking world.

"The new mythologies, which readers undoubtedly need, are constructed by writers through hybridization... of indigenous worldviews with the masters of feminism, of technology with humor, of the essay with science fiction," Carrión's essay continues.

"A distinctive feature of Latin American science fiction is the combination of elements that we experience and therefore write about very naturally," explains Brenda.

"Something that is done a lot is mixing fantasy with science fiction and fantasy not understood in the framework of unicorns or dragons, but rather fantastic literature of a different order," he adds.

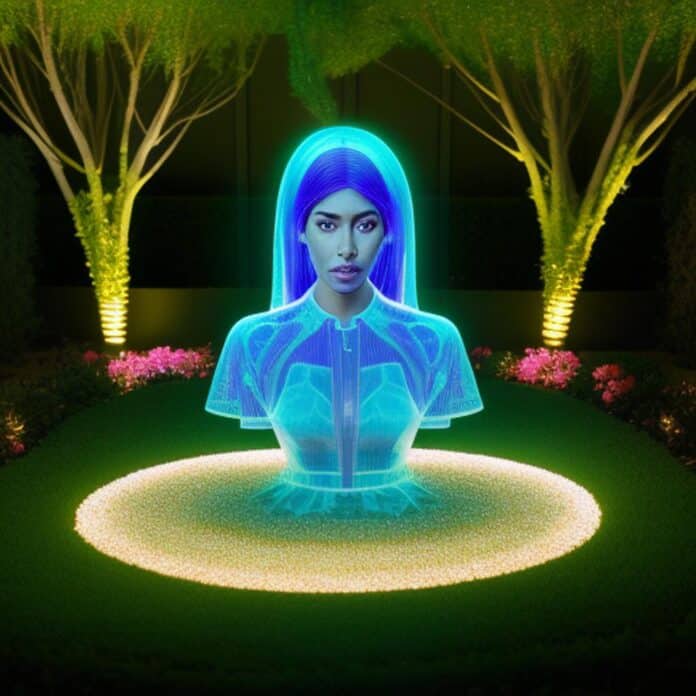

An example in the Mexican context is the story by Gabriela Damián Miravete, “Soñarán en el jardín” (They will dream in the garden), which can be read on the pages of the online magazine latinamericanliteraturetoday.org.

In the aforementioned garden live the pearly silhouettes ‒the “holographic memorial”‒ of women and girls murdered and disappeared in Mexico, in a past that, by the time of the story, has already been overcome.

In a country where at least ten women and girls die or disappear every day due to gender-based violence and domestic violence (official figures are rather conservative), Damián Miravete's story imagines a future in which women organize themselves and stop the murders.

Ursula K. Heise, a professor in the Department of English at the University of California, Los Angeles (UCLA), points out that in Latin America, "what has attracted attention has been the attention paid to social scenarios rather than to science and technology" in so-called science fiction or "speculative" fiction, which is what many prefer to call this type of narrative.

“If you think of people like Ignatio de Loyola Brandao in Brazil, science fiction becomes a way of articulating political critique, right?” Heise explains. “His great novel from 1981, Nao Verais Pais Nenhum, is about a somewhat futuristic Sao Paulo, where the whole Amazon has been deforested. It’s incredibly hot, and it’s all a metaphor for the military dictatorship of the time.”

Heise also refers to the Bolivian Edmundo Paz Soldán who "has thought about a lot of science fiction that arises in the context of having to write about oppressive forms of government under conditions of censorship."

Paz Soldán has written about what is apparently a future society or a society on another planet, but is in fact a veiled criticism of the conditions in her own country at the present time.

In 2005, Argentine Pedro Mairal wrote a novel that has become a cult classic, "The Year of the Desert," in which a force called the elements attacks the city of Buenos Aires, "where chaos reigns, food rots, epidemics break out, and women see their rights curtailed."

"It's hard to know exactly what this is referring to," Heise explains. "But the most plausible interpretation is that it refers to the collapse of the Argentine economy in 2001 and perhaps an indirect way of dealing with the dictatorial past and European colonialism."

looking for answers

Argentine writer Mariana Enríquez, known as "the queen of gothic realism" and winner of multiple awards in Spanish and English, explained it this way during an interview with El Economista de México:

"What is happening in the region, and it is a problem for many horror writers, is that the volume is already very high. We are experiencing a horror that is quite difficult to explain from a realistic perspective. It seems to me that fiction, and especially horror fiction, helps to obtain answers," he says.

The dystopian futures present in much Anglo-Saxon science fiction reflect the growing anxieties that many Latin Americans have long grappled with, Heise says.

"People in the Third World, in the developing world, in the Global South, so to speak, are already experiencing the problems of widespread waste, of climate change, of poverty, of hunger, of desertification, in a way that the Global North is just beginning to experience, but not yet," Heise notes.

And it is there, in that literature born from a complicated present, an uncertain future, and a tradition of fantasy and imagination that goes back to indigenous traditions and colonial and imperialist influences, where perhaps one can feel some echoes of other literary traditions such as magical realism and the inevitable extinction of Macondo.

This report is part of a special series exploring how global societies and diaspora communities in the US are coping with the “polycrisis», a term increasingly used to describe the confluence of current and emerging global crises. It has been funded by a grant from the Omega Resilience Awards.

Read the original note giving click here.

You may be interested in: The battle to ban books in schools sharply escalates