Irma Gallo.

You could start writing this review with the following sentence:

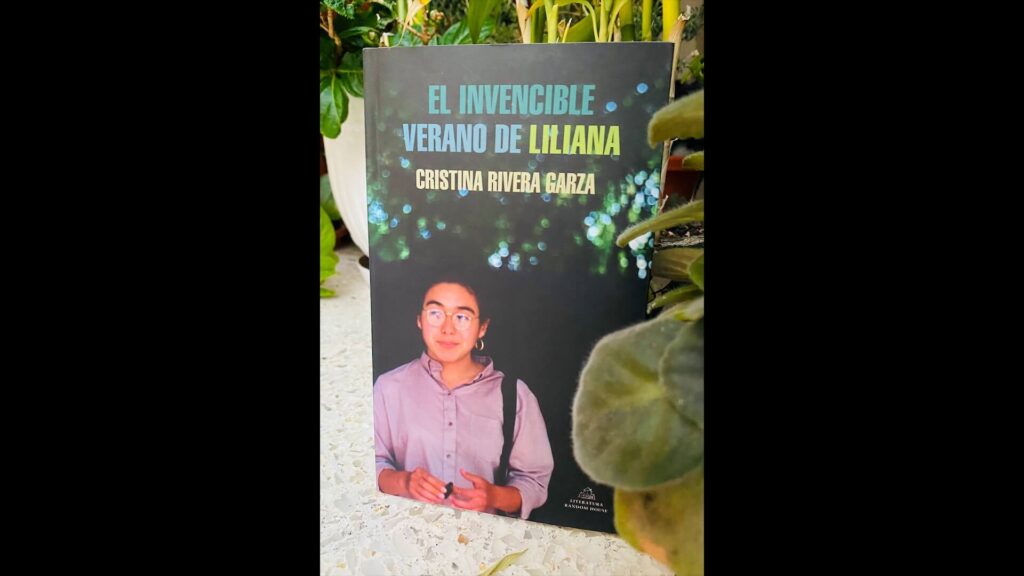

On July 16, 1990, Liliana Rivera Garza was the victim of femicide in the City of Mico.

And although in that year the term feels so far away

You could start writing this review with the following sentence:

On July 16, 1990, Liliana Rivera Garza was the victim of femicide in the City of Mico.

And although in that year the term feels so far away